What do we really know about the universe in which we live? More importantly, perhaps, what can we know?

What do we really know about the universe in which we live? More importantly, perhaps, what can we know?

Brian Greene, a Columbia University physics professor, discusses today, in a New York Times feature article, the consequences of the fact that the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate -- not, as one would expect, at a slower rate. This accelerating expansion suggests that some force -- in addition to the original force of the Big Bang -- is more than counteracting the mutual gravitational attraction of all the matter in the universe. Dr. Greene describes this force as Einstein's posited "repulsive gravitation" or, in modern terms, "dark energy" -- something that is inherent in the nature of space itself.

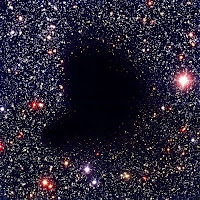

Regardless of the mysterious nature of dark energy, its observed effect is that the universe is expanding, and expanding faster and faster. Eventually, this expansion will result in remote galaxies distancing themselves from each other at a speed faster than light.1 At that point, such galaxies will become permanently invisible to each other. In perhaps 100 billion years from now, our descendents on earth, gazing at the sky through telescopes, will see nothing but the stars in our own Milky Way galaxy.

Dr. Greene notes, somewhat whimsically, that such future astonomers, if confronted with ancient documents from earlier times describing galaxies as numerous as the stars themselves in our own galaxy, will have to decide whether to believe their own observations or the accounts from those documentary relics from the past. Accounts of a sky full of galaxies will seem as dubious to them as stories of the Greek or Hindu gods do to us today.

The moral is clear: we can never learn everything, or even very much, about the nature of reality. What critical information is already unknowable to us today because of analogous shielding of past events? Dr. Greene notes:

We've grown accustomed to the idea that with sufficient hard work and dedication, there's no barrier to how fully we can both grasp reality and confirm our own understanding. ... [But] sometimes the true nature of reality beckons from just beyond the horizon.

When considering how we "know" our world on the human scale, I'm always amazed at how our bodies perceive a narrow band of electromagnetic radiation ("light"), some neurological reactions to pressure on the skin ("feel"), and waves of compression in the atmosphere ("sound") -- and how our brains build a mental image of what lies around us out of this limited data, and how we then confidently believe that we have "observed" reality. How different would the "reality" of life on earth look if we perceived only ultraviolet light? Or x-rays?

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

--Matthew Arnold

Dr. Greene's article makes it clear that we not only are limited in our perception of reality by the limitations of our sensory perceptions and our brain's ability to process all those perceptions that it does receive -- we are limited by the very nature of the universe itself.

We should feel a certain humility when we assert claims of absolute certainty about anything. But of course we don't. And won't.

------------------------------1As Dr. Greene explains it, this expectation does not contradict relativistic limitations. Relativity applies to the motions of objects, relative to each other, within space. "Dark energy" is not causing objects to fly apart within space; it is causing space itself to rapidly expand.

No comments:

Post a Comment